Arms control is almost always discussed within the context of nuclear, chemical, and biological weapons. And this is for good reason. The vast majority of arms control efforts over the past 80 years have focused on finding ways to control weapons of mass destruction. But often overlooked is the fact that arms control has existed for centuries in one form or another. Charlemagne’s grandson banned the export of scale armor in the 9th century, and the Pope banned the use of crossbows (against good Christians) in the 11th century. In the 17th century, France and the Holy Roman Empire banned the use of poison weapons. The list goes on.

More recently, arms control treaties have been intended to end arms races and force some manner of balance between competitors. The various limits on strategic arms agreed to throughout the Cold War are one such example – they sought to find some sort of balance through enforced numerical equilibrium between the nuclear arsenals of the United States and the Soviet Union.

These efforts are hard, and they are growing harder. While a part of this difficulty is surely the degradation of any agreed consensus on what stability is or if states are even interested in stability in the first place – Russia for example appears to be heavily invested in maintaining instability to suit its objectives – one additional problem is that modern warfare is now so technologically complex, multi-domain, and with perilously short time horizons, it is unclear if we can ever really find equilibrium again. Not because we can’t agree on it – but because we don’t even know what equilibrium looks like.

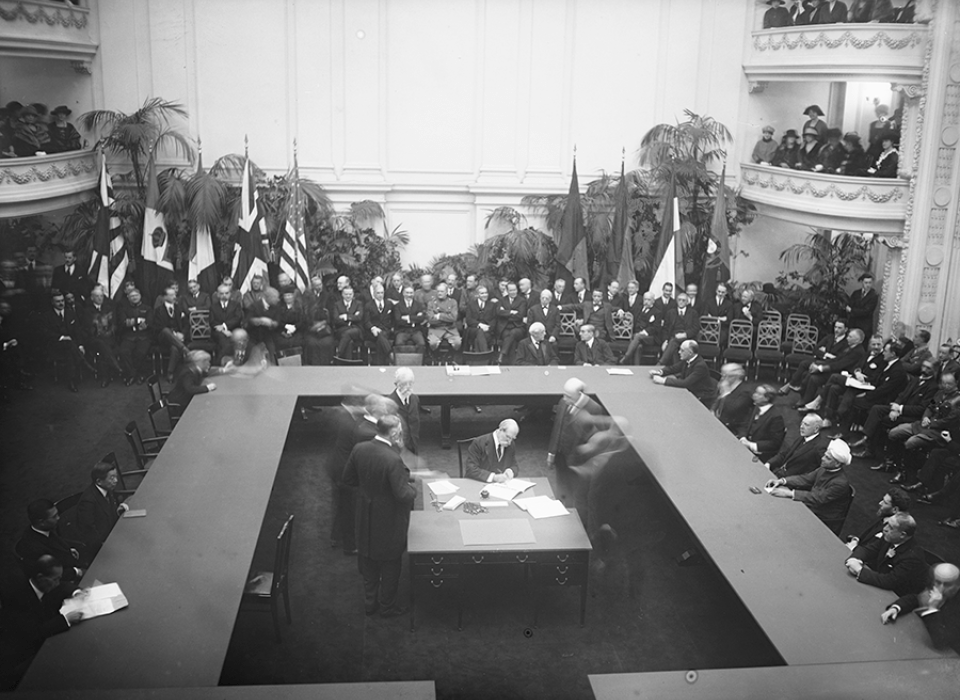

An example of what I mean by this. The Washington Naval Treaty of 1922 was by far the most impactful of the pre-nuclear strategic arms control measures. Instead of simply prohibiting future weapons, the Washington Naval Treaty set hard limits on the tonnage of capital ships and how many each party of the treaty could operate at any given time, as well as limiting the armament of non-capital ships. The goal of the treaty was to interrupt the brewing post-Great War arms race, and it was briefly extremely successful at doing this – America, Britain, and Japan scrapped their latest designs and for a period, the arms race was constrained. This treaty was enabled, in part, by how relatively simplistic the weapons it controlled were.

Consider the ultima regio of the era. The battleship, 30,000 tons of heavy armor and armed with large caliber guns capable of throwing explosive shells out to 20 or 30 kilometers. They are immense and effectively impossible to hide. Deducing the capabilities of each ship was a relatively straightforward matter of measuring the draft, length, and breadth of each ship and the size of its guns. One could simply look at a warship and deduce the size of its armaments and the elevation range of its guns and produce some back-of-the-envelope estimates on its capabilities. This makes finding equilibrium somewhat straightforward – the adversary has forty 14-inch guns, and I thirty – therefore, we are in disequilibrium. Because of this, the Washington Naval Treaty contained no verification scheme whatsoever. The drafters simply assumed it would be easy.

Now consider the ICBM. ICBMs have a defined weight and length, and one could, in theory, do some back-of-the-envelope math to deduce their range and payload. But ICBMs are such monumentally complicated weapon systems, integrated into a mind-numbingly complex battlespace, that the actual determinants of equilibrium are both incredibly numerous and effectively impossible to accurately assess without real combat experience. What is the accuracy of the missile? What is its yield? How advanced is its fusing system? To what degree does the missile’s fuel grain affect its range performance? What sort of angles of attack can its RV achieve? How quickly can it launch? Is it survivable? Are its command-and-control systems survivable? Do those systems have redundancies? How insulated are they from cyberattacks? What are its ground-penetrating capabilities? Does it have decoys? Can it maneuver? If the missile is mounted on a submarine, how hard is it to detect? And so on. These questions are then combined with questions about the state’s conventional capabilities, its ability to target strategic systems with long-range precision munitions, its cyber capabilities, its space-based capabilities, its anti-submarine, and so on.

The result is a complex, multi-domain environment in which it is effectively impossible to accurately assess equilibrium in any real sense of the term. For many years we have papered over many of these concerns with the invention of accounting fictions intended to support the idea that equilibrium in strategic launchers is in some way representative of general strategic equilibrium. These fictions are rapidly falling apart. States can now blind the enemy in space and cyberspace and launch conventional attacks on command-and-control nodes and strategic forces. The strategic nuclear level of war is no longer capable of being separated from the conventional level of war due to these technological complexities, and the result is a general unease in all nuclear states of their strategic position vis-à-vis their adversaries. There are simply so many unknowns about so many advanced kinetic and non-kinetic weapon systems that no one really has any idea about where the real equilibrium lies.

The writers of the Washington Naval Treaty were confident of their ideas on where the equilibrium was partly because the members had recently fought two major naval engagements – the Battle of Tsushima and the Battle of Jutland – which revealed the real equilibrium. This is, for what should be obvious reasons, a problem for nuclear conflict, as not only has there never been a peer-to-peer nuclear engagement, but if one were to occur, it could be our last.

The end result of this is that arms control is growing harder. We have created a technological labyrinth of such breathtaking complexity that we, trapped inside it, cannot ever glimpse the whole picture. If any future arms control regime on strategic weapons should by some miracle grace us again, it will likely have to be kept as general and light on details as possible to avoid the technological cans of worms produced by the modern battlespace.

Leave a comment