Recently I’ve seen a couple comments on how Russian success in the domain of nuclear coercion is likely emboldening China. I’m always skeptical when “emboldening” gets thrown around, as in 99% of cases you’re relying on an effectively unevidenced causal mechanism. You’re basically saying “X is working for Y country, therefore Z country will use it as well” without doing anything to prove that countries Y and Z actually view X in the same way. The case of Russian coercion against the West over Ukraine and what China may be taking away from Russian coercive efforts is a very good example of this problem, as Western analysts appear to have a much higher opinion of the effectiveness of Russian coercive actions than the Russians themselves have. This is a large problem, as China is almost certainly paying more attention to what the Russians are saying about their own operations. As Dima Adamsky has written in his excellent article, Russian coercive actions have broadly failed to prevent a wide array of Western actions, and the Russians complain loudly about this fact.

Let’s break it down: what Russian coercive actions have succeeded over the past three years? Russia has succeeded in producing great delays in the delivery of particular kinds of weapon systems like the ATACMS. In this way it has generated some modest success in deterring the West from engaging in some types of actions. But it has completely failed to compel the West to cease actions once those actions have been broadly agreed to by the NATO coalition. Once deliveries of ATACMS and other long range strike systems started, Russia failed to compel their termination, even with explicit threats over the matter and demonstration strikes like the Oreshnik strike last November.

Russian military thinkers are aware that their strategic threats have not been seen by the West as credible for deterring low level actions like weapon deliveries, and if Chinese analysts are reading the Russian journals (they are) this will be the overarching lesson they will likely take from the war: that strategic threats are good for deterrence, but that compellence is much harder. How will Chinese thinkers apply this to their situation? My guess, as we don’t have that much hard data, is that they will conclude that the window for deterrence is very small, and that they must deter low level actions quickly and decisively to prevent adversary salami slicing. If China were to be engaged in a similar conflict (say, for example, with India or Vietnam) and the United States decided to engage in arms deliveries to those states, China would have to act very quickly to deter those before they even begin.

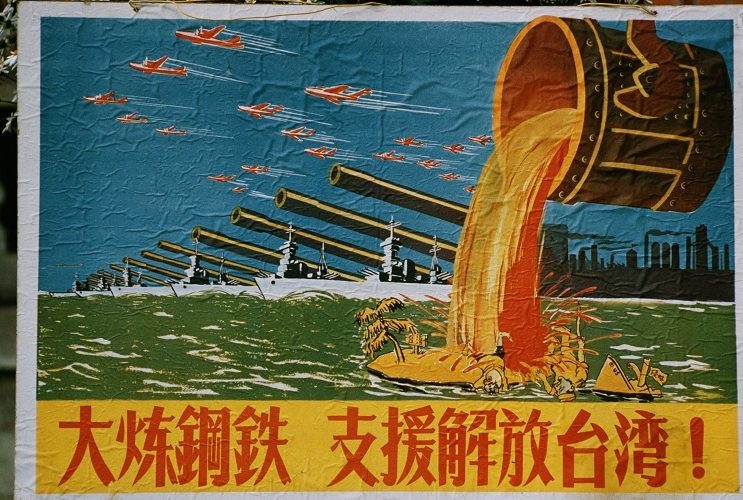

I personally believe that the application of Russian coercion lessons to the Taiwan invasion case is less clear as that’s a peer-to-peer war situation and the deterrence requirements are much much greater, but the same broad lessons could apply. China would need to move very quickly to deter any low-level action in support of Taiwan on the United States’ part. Perhaps this makes a “quick invasion” with little strategic warning more attractive to Chinese planners. Time will hopefully not tell in this particular case.

Leave a comment