So rarely these days do we get good shots of Chinese missiles. Aside from the occasional shot of a DF-26 IRBM brigade doing some exercise somewhere, or some DF-11s SRBMs practicing around Fujian, actual new footage of important People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force (PLARF) operations have become something of a small rarity. Which is why I was so pleased when the PLARF fairy decided to reward all the good little OSINT analysts with some very nice footage of a DF-31AG launch. This single picture has cleared up a lot of confusion in open source about the DF-31AG and the trajectory of the entire DF-31 family of missiles. We’ll start with the missile itself (a section that turned out to be way longer than I expected, but what do you want from me? I’m a missile nerd), and then move on to why China has decided to do this now.

China’s two families of solid-fueled ICBMs consist of the DF-31 and the DF-41, the latter being a much bigger MIRV-capable missile. The DF-31 family of ICBMs includes the DF-31, DF-31A, DF-31AG, and possibly, a future DF-31B. The DF-31 was China’s first mobile ICBM, although the Chinese don’t call the base version of the system, which has now been retired in favor of the DF-31A, an ICBM. It didn’t have the range to hit the United States from deep inside China, although China did place one DF-31 brigade 55 kilometers away from the North Korean border that could have theoretically hit Seattle.

The DF-31 was mobile, but barely. It had a comically large number of support vehicles, was not off-road capable, and appears to have needed pre-positioned sites to fire. The original version required a massive number of cables which the original version of the system carried around in big, six-wheel tour buses with the seats ripped out.

This problem got better as China improved the DF-31 system, and major modifications to the DF-31 resulted in the DF-31A, which is a true ICBM capable of reaching most of the United States. The DF-31A adds a shroud that covers a lot of the third stage (which led to some very off assessments as to how much fuel the first stage could carry, by the way) and an interesting drag-reduction system at the tip of the nosecone intended to create a bow shock and reduce drag on the rest of the missile body. You can see it at the tip of the missile in the image below.

Then in 2017 China unveiled the DF-31AG. The DF-31AG uses a much larger TEL (seen below) than the older truck and trailer setups the DF-31 and DF-31A had, and a weirdly big canister, which led to a lot of questions on what updates China had given the missile. The China watching space was immediately awash with claims that the DF-31AG was a MIRV capable missile that was physically bigger and capable of carrying much heavier payloads than the 31A variant – hence, the larger canister. United States government documents like the National Air and Space Intelligence Center’s 2020 Ballistic and Cruise Threat Report listed the number of warheads the DF-31AG carried as “unknown,” and every year the Department of Defense’s China Military Power Report listed all the different versions of the DF-31 (DF-31, DF-31A, DF-31AG) as if there were significant differences between the A and the AG.

Part of the mystery was solved when the DF-41 was unveiled in 2019, and we immediately noticed that the DF-41 used the same TEL chassis and a canister with the same diameter as the DF-31AG – it’s just that the DF-41’s canister is longer. Its likely that this is simply a cost saving measure. China wanted to modernize the DF-31A and move its launch control process to more modern systems, and so it seems the DF-31AG shares the same onboard consoles for launch control as the DF-41. This was confirmed when we got a look at one of the PLARF’s ICBM training facilities, and sure enough, both the DF-41 and DF-31AG appear to use basically the same consoles.

Then there’s the small problem of the DF-31AG’s name. Why was it not called the DF-31B to distinguish it as a major modification of the DF-31? “AG” implies that the missile remains fundamentally an A, but with some sort of other modification or improvement. Sure enough, when China did a big exhibition in Beijing about all their ICBMs, they list the DF-31AG as an improvement on the DF-31A – but not a new missile.

Then there were subtle changes to the way the DF-31AG was talked about in government sources. The CMPR stopped writing out the members of the DF-31 family, and simply listed all DF-31s as if they were the same, likely because at this point the DF-31 original mod had been retired and the Department of Defense began recounting all DF-31As, AG or not, as effectively the same missile. We didn’t get any indication after 2022 that government sources believed that the missile inside the DF-31AG TEL was significantly different than the missile inside the DF-31A TEL.

So at this point Jeffrey Lewis and I were pretty confident that the DF-31AG was not some new missile but simply an improvement on the existing DF-31. This makes sense economically. Imagine you are a Chinese nuclear missile designer, and someone from the PLARF shows up at your door and asks you for a MIRV-capable version of the DF-31A. You go to your desk as begin drawing up the plans: the larger weight of the multiple warheads and the bus would require more thrust to get it off the ground so you increase the size of the first and second stages. And while you’re at it, the DF-31A has a pretty antiquated guidance system, so why don’t we rip that out too while we’re at it. And the much bigger bus is also going to require significant redesigns to the shroud and the third stage. And then you will realize what you’ve just done: you’ve designed a DF-41. Adding the kind of capabilities that would be required to build a MIRV’d DF-31 would require an entirely new missile that looks an awfully lot like one China is already building.

By the way, if the people confidently claiming the DF-31AG was going to be MIRV’d had stopped and considered why its designation starts with 3, they likely could have reconsidered the entire argument then and there. The DF-11 and DF-15 missiles have one stage. The DF-21, DF-26, and DF-27 missiles have – you can probably already see where this is going – two stages. The DF-31 has three stages. And the DF-41 has three stages…and a bus.

But despite our confidence, we didn’t have one thing: an image of a DF-31A looking missile coming out of a DF-31AG TEL. And guess what the PLARF was more than happy to provide to us last month?

Sure enough, that thing looks a hell of a lot like a 31A. It’s at this point very difficult to measure because of the angles, but I’ve compared the thing extensively to my collection of DF-31A imagery, and everything appears to be in the correct places. Most importantly, we don’t see any changes to the pointy end that would cause us to consider that the missile is packing a much bigger payload. This has, at least in Jeffrey and I’s opinion, settled it. The DF-31AG is almost certainly simply a DF-31A that’s gotten a makeover and a very modernized ground support equipment package.

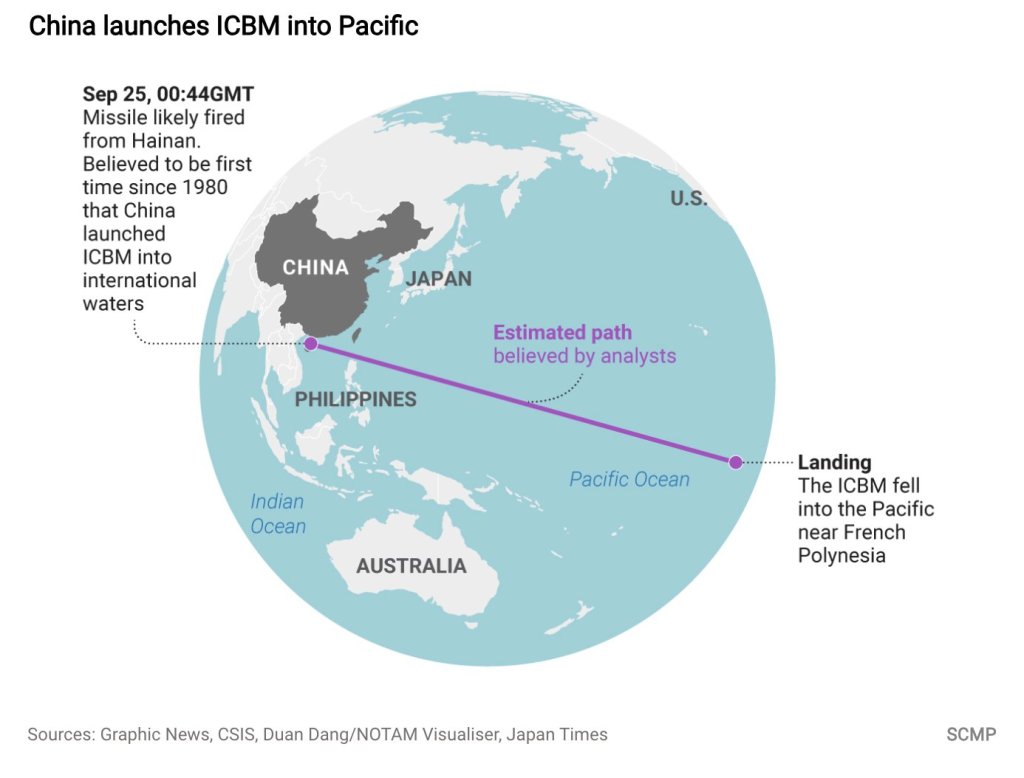

Now on to the test and why China may have decided to do it now. On September 25th, China launched a DF-31A ICBM from Hainan Island, where DF-31As are not native. The missile flew over the ocean between the Philippines and Taiwan, and splashed down over 10,000 kilometers away near French Polynesia.

Three explanations have been put forward, one by myself, one by others including the always insightful Tong Zhao, and a third explanation that’s been put forward by some others, one I don’t take much stock in.

Let’s start with the purely technical reasons why you’d do this. This is the first time China has tested an ICBM over the Pacific since the famous 1980 test of the DF-5 ICBM. The problem that China has with testing ICBMs is that ICBMs are supposed to go a long way, and China doesn’t have that much space to work with. What China generally does is launch into its western desert, and has impact sites that are about 2,000-3,000 kilometers away from their main ICBM testing site at Wuzhai. This is sub-optimal if you are testing missiles that are supposed to travel 13,000 kilometers. You could launch over the Pacific, but there are a lot of these little annoying countries like Japan and the Philippines that might get upset if you do that, so China has used this option sparingly.

Why does the range you are testing the missile at matter? Because when you shorten the range, you have to change the trajectory. Solid-fueled missiles generally can’t change how much thrust they produce. Once the motor is ignited, its gonna go, whether you like it or not. So when you only have 3,000 kilometers to work with, you have to fire the missile basically straight up into space instead of firing it on what we call a “minimum energy trajectory” (MET) that would be shallower and take it to its maximum range. Below is a graphic from Reuters that I think shows the difference really well, discussing in this instance the North Korean case.

This matters because it’s a different sort of stress for your reentry vehicle. When you fire a missile at a high arc, your reentry vehicle comes down screaming through the atmosphere at high speed, and on reentry is going to be subjected to extremely high heat, but for a short amount of time. But on a shallower arc, your reentry vehicle is going slower, but is reentering the atmosphere for a longer period of time, meaning the the total amount of heat you are subjecting the heat shield to will be higher. This is why the United States almost always tests ICBMs on an MET – it’s a much more realistic test of the system. Its also the reason former members of the PLA are giving.

So that’s the technical reason. Likely the PLARF has extracted useful data here on the performance of the DF-31AG. What about the political reasons? Tong Zhao has put forward the credible argument that this test was conducted partly for political purposes. Several major scandals have rocked the People’s Liberation Army Rocket Force, and many prominent generals have been unceremoniously sacked, allegedly over corruption issues. With China’s main deterrent force so de-legitimized, Beijing may have decided it needed to reestablish the credibility of its nuclear deterrent forces in the eyes of the international community. The fact that they selected a DF-31AG for this mission may be particularly telling: according to former head of United States Strategic Command, Admiral Charles Richard, the DF-31 will be the missile China will use in its new silo fields.

I’d add another important consideration: that the PLARF may need to re-establish its credibility in Beijing. With so many corruption scandals, it may be that the PLARF wanted to communicate to the Central Military Commission of the Communist Party that they were still up for the mission. Communicating this may be especially important in light of the fact that if the PLARF can’t prove it can be relied upon to credibly maintain China’s deterrent forces, there are alternatives. China’s Navy and Air Force are both expanding their nuclear roles, and even the Ground Force is getting into the missile game, although their forces are entirely conventional. All of those branches will be keen to slice off bigger and bigger chunks of the Rocket Force’s immense budget.

The last argument I’ve heard which is by far the least convincing is that this was intended to be a specific threat to the United States over its missile deployments to the Philippines. The United States has deployed the Typhon weapon system to the Philippines, which the Philippines now wants to host indefinitely. The trajectory of the DF-31AG test passed very close to the northern shore of the Philippines, and dropped stage debris on either side.

I’m very skeptical of this argument as the threat isn’t really linkable to to the thing China may be trying to compel the United States to remove. The famous historical incident for comparison is Nixon’s Operation Giant Lance, in which the United States attempted to threaten the Soviet Union with B-52 bomber flights in order to compel them to put pressure on the North Vietnamese to sign a peace deal. According to most historical sources, the Soviets did not really understand that the bomber flights were linked to the Vietnam issue, even when Kissinger pressured Soviet ambassador at the same time.

Similar problem here. Is an ICBM test really a great way to respond to a conventional medium-range missile deployment? Likely not. It’s not like you’d use a nuclear ICBM to hit a small conventional target 1,000 kilometers away from your other conventional missile forces which would be happy to do the job. It would be a remarkably unusual thing for China to do to signal displeasure with an ICBM test when the bomber force has been generally the force China has relied on for signaling, a force that would be more casually linked to a conventional missile deployment. Using an ICBM for that is a little like threatening to use the 101st Airborne, in its entirety, to stop a bodega robbery. Its simply not a credible use of forces. Also, we don’t see a companion information campaign in Chinese media, which is pretty standard for Chinese compellence campaign.

We don’t know precisely why China has decided to test now, but those are some explanations. I wouldn’t overreact to this sort of thing, unless I’m wildly wrong and there is some very serious back-channel compellence going on. Considering China warned the United States government before doing this, it may actually be a good thing as it allows for a little more exchange of information in the future.

Leave a comment